JAPANESE RED, PURPLE CORAL AND JADE CIPHER

GO BACK, USE PURPLE, OR HEAR THE PURPLE MACHINE RUN

INSTRUCTIONS ON USING THE PURPLE MACHINE ON THE MAIN PAGE

Notes and corrections are with the grateful assistance of Geoffrey Sinclair

Not having a written language of their own, in the third century AD, the Japanese began to adopt Chinese ideographs, symbols or pictures which represent an idea or an object, and use them for words of similar meaning in their spoken language. Each ideograph represented one picture, one idea, one meaning and hence it was not difficult to apply the ideographs to Japanese words with the same meaning (Deadly Magic 18). In the ninth century they adopted Chinese pronunciation of compound words made up of several ideographs. This system required all Japanese to learn four or five different pronunciations or readings for each ideograph; there were thousands of ideographs in use.

In order to simplify the written Japanese, Japan also invented two phonetic alphabets each consisting of fifty letters: katakana – block letters and Hiragana – cursive writing (Deadly Magic 19). Katakana was the most abbreviated and simple, was typically used to write foreign words. Hiragana, which is more directly related to Chinese, was to be used for native Japanese words and concepts. All attempts at introducing the Latin alphabet into Japan failed.

It is because of this complex, engrossed language that Japan didn't use Morse code for communication. Instead they keyed messages, developed by the Imperial Navy, according to the syllable of the word in katakana (Prados, 9). As a result, the code contained twice as many dots and dashes. Used prior to and during World War II, it was Japan’s own form of Morse code.

When the U.S. Seized the Philippines in 1898, Japan-US relations were tarnished for the first time. The Imperial Japanese Navy saw the US’ westward movement as "squeezing and poisoning Japan." The relationship worsened at the Washington disarmament conference of 1922 because the US forced Japan a lower warship ratio than they wanted. Americans sought a way to figure out what Japan was planning.

In 1923 the United States Chief of Naval Operations told the Asiatic and Pacific fleet radio operators to listen for Japanese messages. . .perhaps he was unaware that they were transmitted differently than all other. Either way, the operators were able to teach themselves to recognize and intercept Japanese radio communications. One Philippine operator, Harry Kidder, learned katakana syllable through the teachings of the Japanese wife of a shipmate. Kidder was then able to teach himself the telegraphic equivalent of each symbol and thus began to translate the intercepted Japanese messages. At first, intercept operations were only handled on a few ships in the Asiatic fleet.

A few others at the Asian station learned katakana as well, but the translations by all were very haphazard.

In 1918 a Japanese codebook was found and by 1921, it was completely translated by the Office of Navy Intelligence. Only a few copies of the Japanese fleet code were made by the Americans who code named it the "Red Book," and passed it on to the Director of Naval Communications. As a result, the Director then saw the need for a radio intelligence service to be developed. A school was set up in Washington to teach selected radio operators katakana and the Japanese telegraphic codes. When the school opened in 1928, Chief Kidder was the teacher where he graduated three classes. Eight graduates from the school were sent to Guam where they established station BAKER.

Meanwhile, in 1924, a big step was taken to organize transcription when the US bought Japanese typewriters. As a result, the first shore-based intercept station was built in Shanghai that year. The main focus of this station was the diplomatic radio network that served the Japanese consultants throughout China. In the meantime, self-trained operators in the Marine Corp in Beijing also focused on this network. Known as station ABLE, this unit was abandoned after eight years of service in 1935 due to the Japanese threat and lack of personnel. Then the responsibility for the diplomatic network was shifted to the headquarters of the Fourth Marine Regiment in Shanghai. This station, equipped with lots of Navy intercept operators trained in Japanese, was thus renamed ABLE.

In 1930, the men at station BAKER were able to deduce from intercept patterns alone that Japan's entire fleet including reserves had set sail and were engaged in some sort of massive exercise. In fact, these men were right. The Japanese navy had called up its reserves to participate in a practice attack. The US Navy stationed in Tokyo had no idea. Station BAKER sent these intercepts to Washington to be translated. The US government cryptanalysts used the "Red Book" to slowly aid them in the decryption process. Enough was decoded for the Americans to realize that the detected activity was a practice invasion of Manchuria.

The slowness of the decryption of these intercepts led the United States to realize the inadequacy of its facilities for decoding and intercepting messages. Intercept stations needed to be built in Hawaii and in the Far East to aid those in the Pacific Theater. These stations needed to employ an abundance of cryptanalysts, Japanese linguists and intercept operators.

Also in 1930, the Japanese changed their "Red Book." Unfortunately, this new Blue Code was considerably more complex. It was a "four-kana" code unlike the Red Code’s "three-kana" code. The Japanese also complicated this code even more by inserting material from other sections on each page. The result was that the progression of the vocabulary from the old code was broken up making it more difficult to crack. For the next five years, American cryptanalysts worked on deciphering a new codebook, led primarily by the Radio Intelligence Officer of the Asiatic Fleet, Joseph Wenger. There were other available communication sources as well. The Navy attacked Japanese naval codes – for administration, merchant ships, logistics, intelligence – and several cipher machines. Traffic analysis was also available when code breaking failed. Traffic analysis involved an "organizations structure and operation from message routing, message volume, call signs, and operations’ chatter." One of the key tools used is direction-finding; it locates a radio transmitter and through connections can tell where a ship is. Other techniques can be used to plot a ship’s course and speed. Also, by studying the call signs, you can determine which stations are talking. Also increased volume in a certain area can represent increased activity. The hardest part of breaking a code is getting started. One cryptanalyst explained "It first off involved what I call the staring process. You look at all of these messages that you have; you line them up in various ways; you write them one below the other; you write them in various forms and you stare at them. Pretty soon you’d notice a pattern; you’d notice a definite pattern between these messages. This is the first clue." Using all other forms of communication and prediction techniques, he was able to guess and correctly determine Japan's actions. He then used these predictions to translate the signals received during the blackout. He produced a 115-page report that served as a basis for the "Blue Book." The Commander in Chief of the Asiatic Fleet was extremely impressed by Wenger's work and he requested an intercept station in Manila Bay to serve as the "ultimate defense" to protect the surprise attack.

Five graduates from Kidder's classes, meanwhile, had been sent to the Philippines to set up an intercept station in Olangapo. They called themselves station CAST and were moved to Mariveles, then to the Navy Yard in Cavite, and were finally stationed in a bombproof tunnel built for the US Navy at Monkey Point on Correigidor in 1940. In 1942, station ABLE was closed and its personnel and duties were given to station CAST. CAST provided major intelligence support for the Asiatic Fleet. They had interception and cryptanalytic capacity, a direction-finding capacity, as well as extensive liaison with fleet headquarters. Stations CAST’s "claim to fame," however, was that it was the first United States communication unit to track a Japanese warship entirely by monitoring communications. By 1941, station CAST had forty-one radiomen, nine yeomen, and ten crypto-analytical personnel (Prados 83).

In

1936, another station was being built by Thomas Dyer on the windward side of

Oahu, station HYPO, and a new decryption site was created in the basement of the

administration building in Pearl Harbor. Having more staff than station CAST,

station HYPO employed sixty-nine radiomen plus boasted a significant

crypto-analytical facility.

The

Japanese cipher machine which the American cryptanalysts codenamed CORAL is

perhaps the easiest to understand of the three code

machines they employed.

All three machines were built from common telephone stepping switches. These switches had six input wires. Each wire was connected to a wiper, and each wiper could make contact with one of twenty-five terminals. All six wipers moved together, and each one had its own set of 25 terminals to contact.

A solenoid controlled the movement of the wipers. When a current pulse was fed to it, the wipers advanced one position, except that, if the wipers were already at position 25, a spring caused the wipers to go back to the first position. Thus, although the 25 terminals were arranged in a semicircle, the switch acted as though they formed a full circle, with stepping in only one direction.

In CORAL, a stack of five stepping switches did the same job as a rotor would do in a Hebern rotor machine. 26 input wires carried current to 26 outputs, in 25 different ways. The alphabets for each of the 25 wiper positions, unlike the alphabets for the different positions of a rotor, were completely independent and unrelated.

JADE was just about the same as CORAL, except that it was used to encipher messages written with the Japanese katakana syllabary, which has 48 symbols. Thus, it added a shift key to the keyboard. This shift key accompanied a 25-symbol alphabet, which gave equivalents to the 48 kana and the two diacritical marks used with katakana.

PURPLE, the earliest of the three machines, had a somewhat stranger structure. A plug board selected 20 letters of the alphabet to be enciphered through banks of four stepping switches. The other six letters were enciphered by means of only one stepping switch. This division of the alphabet was easily detected through frequency counts, and was perhaps the most serious weakness of the machine. (Another very serious weakness, and also a strong contender for the title of "most serious weakness", was the fact that the stepping switch banks were, for obvious reasons, not removable, so one could never perform the operation equivalent to changing the rotor order.)

The following diagram:

attempts, with many parts omitted, to illustrate how PURPLE worked. The plug board reassigned letters for both input and output. The stepping switches only have fifteen tick marks around them - representing the 25 contacts each wiper actually has. For only one wiper position for each switch or bank of ganged switches, the scrambled arrangement in which the wires are connected to corresponding wires in the next stage are shown. However, the 20 versus 6 division is easily visible in the diagram, as is the general arrangement of the device.

The three banks of stepping switches advanced in the traditional odometer like fashion; when the fast one advanced 25 steps, the medium one would advance one step, and when the medium one advanced 25 steps, the slow one would advance one step. A switch allowed all six possibilities of which bank was fast, medium, or slow to be selected.

The wiring of the plug board was part of the daily secret key of the machine, as was the pattern of stepping switch bank movement. The starting positions of the stepping switches for each message were communicated by an indicator. Both the plug board wirings and the stepping switch start points came from a book which contained all the possibilities that were used, which were limited in number compared to all the possibilities that could be used with the machine.

Purple was an intricate, complicated cipher machine, a complex adaptation of the German's Enigma machine. Cipher machines, which were first used in World War I, can complicate encipherment of plaintext by performing innumerable enciphering operations, easily and with great speed, making enemy decoding extremely difficult. Breaking a complicated cipher produced by a rotor machine is, however, possible. A crib or plaintext for a number of cipher messages, makes this task much easier. Also, the "indicator system" which is the method by which the sender notifies the recipient of the starting rotor positions for each message. By having enough overlapping cribs, it is possible to link the pieces together nullifying the effect of the rotors. This can make the solutions of the coded messages trivial.

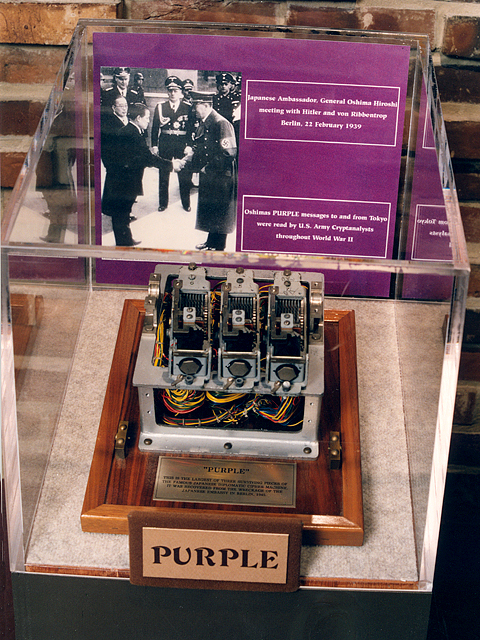

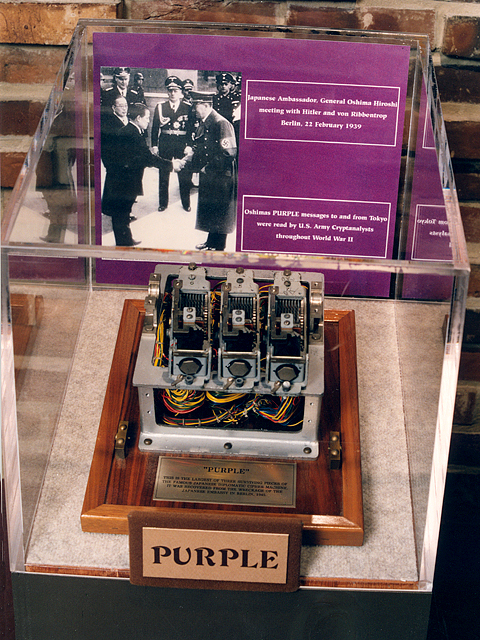

Physically,

a PURPLE machine consisted of two electronic typewriters separated by a plug

board and a box containing the cryptographic elements in a series of relays

within an intricate network of wiring (Deadly Magic 63). The plug board had a

plug for each letter of the Roman alphabet. PURPLE simultaneously recorded

plaintext and cipher text. This double machine super-enciphered alphabets, in

other words, repeatedly enciphered the text, with a multitude of manipulated

versions (Deadly Magic 64). Many millions of cipher alphabets of 26 letters were

available for substitution ciphers. The reoccurrence of a word in its original

enciphered text took place about one in 100 signals. Similar to the Enigma

machine, Purple would not encipher any letter to itself. More specifically, an

"a" entered on the keyboard would never be outputted as an

"a." This is why Japan was so fervent in their beliefs that PURPLE was

unbreakable.

The United States was in a bind, they knew that they would need to create a replica of a PURPLE machine, a "shadow" cipher machine, in order to break Japan's newest code. In August 1940, the team lead by William Friedman, senior cryptanalyst, reconstructed a "shadow" of the PURPLE machine. For the following twenty months, US cryptanalysts experimented with wires and switches of the wheels of the "shadow" machine. This was complicated because the positions of the plug board connections were unknown, and the daily starting positions were unknown as well. Several months into experimenting, it was discovered that the starting keys for each day in a ten day period were related. Operators changed the key to form that of the next nine days. The cryptanalysts involved in breaking Purple worked to match "proposed plaintext", a guess as to the text of the original message, that were simultaneously received in Red and Purple to determine proposed plaintext, because they could decode the Red message.

Two major breakthroughs occurred in the PURPLE deciphering dilemma. First, because Japan guarded their PURPLE machines dearly, they did not put one in every diplomatic office; machines were only put into twelve of the Japanese embassies. Therefore, this helped the US cryptanalysts because, since Japan needed to provide some of the same messages to every diplomatic office and embassy, they were forced to use PURPLE and other cipher codes to transmit these messages. Many of these other cipher codes were already broken by the United States. Thus the Americans were provided with the plaintext corresponding to the PURPLE signal. In other words, it provided the Americans with a crib.

Second, Americans staged an electrical failure at the Japanese embassy in Washington and two agents of the American Signal Intelligence Service, posing as electricians, were able to sneak a peek at the actual PURPLE machine. They were able to alter their "shadow" machine according to the information relayed from the agents.

The first fully intelligible message was recovered on September 25, 1940. The break into Purple was especially notable because the machine was even more sophisticated than the German’s Enigma machine, but also, the code was solved entirely by mathematical analysis. Furthermore, the British analysts who solved Enigma could rely on advances made by French and Polish experts…the Americans solved Purple completely on their own.

The

"shadow" machines proved to be so skillful that Americans were able to

receive the decoded message before the Japanese embassy. After a while,

Washington was reading fifty to seventy-five Japanese messages per day.

If the Japanese knew that the United States’ cryptanalysts had cracked Purple, they would change the code immediately. For obvious reasons, the U.S. wanted to avoid this at all costs (Prados 165).

So after PURPLE was broken in 1940, the United States faced another dilemma as to who should know and who should read the decrypted Japanese signals. The following thirteen people were given viewing rights: President Roosevelt, Secretary of State, War and Navy, Chiefs of Staff of Army and Navy and the Intelligence and War Plans Chiefs of the Army and Navy. The obvious dilemma is that if too many people knew that the Americans had broken Purple, word would leak out and Japan would change the code. This would shut the Americans out of all communication interception.

The

next obvious question is, of course, with all this information and the

successful break into Purple, shouldn’t Washington have known about the attack

on Pearl Harbor?

The short answer is no.

These are some notes from others on Purple:

Purple

was a cipher used by Japan during

World War Two to code diplomatic messages to various embassies throughout the

world, not military traffic. The

military deliberately kept the attack information from the diplomats. Even the

final 14 part message to the US spoke of no further point to negotiations, it

was not a declaration of war.

It had also not helped that some in

US Army intelligence, noting the deadlines for negotiations in the Japanese

messages chose to predict war would occur on Sunday 30 November 1941.

Another

reason is the Japanese consulate in Hawaii, unlike the missions in major world

capitals and in Hong Kong, Manila and Singapore, did not receive a Purple

machine, it continued to use the older codes, and these messages were treated at

a lower priority in Washington given they were not in the main Japanese code

system. The biggest clue in all the diplomatic traffic was a cable to

Hawaii on 24 September 1941 wanting regular reports on the warships in Pearl

Harbor and their locations, and the reply (copied to San Francisco) giving the

chosen system on the 29 September 1941. The intelligence appreciation made in

Washington, which was decoding the consulate traffic and cracked these two

messages on 9 and 10 October respectively, was that it was an unusual message

and that it could be a device to cut down on radio traffic, a plan for sabotage,

a plan for a submarine attack or a plan for an air attack.

The decision was taken not to notify Pearl Harbor of the signals.

The Japanese were receiving regular ships in harbor reports from their

diplomats around the Pacific but no others were asked for ship locations. The Japanese message later became known as the “bomb

plot” message, after the attack and is considered the most obvious lost

opportunity to at least put Hawaii on a higher level of alert. However it should be noted in the weeks before the war

reconnaissance from Hawaii concentrated on the approaches from the closest

Japanese bases in the central Pacific. Since

the USN had not learnt of the recent advances where the Imperial

Japanese Navy (I.J.N.) had learned to refuel ships at sea and that it

knew 3 of the I.J.N. fleet carriers lacked the range to sail to Hawaii and

return from Japan, the USN understood approaching from the central Pacific the

only way for the I.J.N. to launch a major strike against Hawaii.

Without enough reconnaissance aircraft to mount a 360 degree search and

needing to preserve the scare aircraft the searches had to be restricted.

"The

breaking of Purple, though unable to prevent Pearl Harbor, later yielded

astonishing insights into Hitler’s plans, gleaned from the messages of the

Japanese ambassador in Berlin; All of this noticeably shortened the

conflict" (FA 151).

Cryptology was a key factor in the US’s victory in WWII. One expert stated that it shortened the was by a year. It didn’t take long for the US and other nations to realize that cryptanalysis is "the cheapest, latest, and truest source of information" (Kahn, 613). Cryptology became one of the world’s most important sources of secret intelligence in World War II. Vice Admiral Walter S. Anderson, the former director of Naval Intelligence summed it up best when he said, "[Cryptology] won the war!" (Kahn 613).

Some sources claim that American cryptanalysts had cracked the Purple code detailing the attack on Pearl Harbor prior to December 7, 1941. It was also suggested that by December 6, Washington had a message that contained the information that Japan and Germany were prepared to declare war on the United States. Washington allegedly remained silent in order to protect the secret of the Purple code. If the Japanese knew that the United States’ cryptanalysts had cracked Purple, they would change the code immediately. For obvious reasons, the U.S. wanted to avoid this at all costs (Prados 165).

But in an interview with Captain Joseph J. Rochefort, USN, he insists that the cryptanalysts at station Hypo (Rochefort's unit at Pearl Harbor), are not to blame for the attack. He says "an intelligence officer has one task, one job, one mission. This is to tell his commander, his superior, today, what the Japanese are going to do tomorrow. This is his job. If he doesn’t do this, then he’s failed." According to Rochefort, he failed at Pearl Harbor.

He offers two reasons for the failure: One, they only had about five months to get themselves reorganized, and two, radio equipment was being withheld and sent to Europe. He explains that on December 7, the cryptanalysts were running information and supplies back and forth from the intercept station which was six or eight miles away. The only way to communicate with the transmitter site, called CXK, was by sending a jeep. This wasted a couple of hours each way. Rochefort also claimed that the wire system was severely inadequate. "It’s like having a million-dollar organization with a ten-cent stamp communications system," explained Rochefort. He claims that on December 1, the Japanese changed a major part of the communication system that kept the Americans from translating and understanding the messages. So although the volume of messages transmitted suggested that something was about to occur, the cryptanalysts couldn’t read them.

An additional source explained that it wasn’t until eight days later that the messages were fully deciphered and translated. But the problem that occurred with Pearl Harbor wasn’t due to intelligence, it was because of policy. Because there were a limited number of resources at this station, the high-level diplomatic cables received priority. The radio intelligence unit was instructed to work diligently on the Imperial Navy’s Admiral Code rather than deciphering diplomatic codes. Furthermore, the bomb-plot messages were deciphered in Pearl Harbor and not in Washington. Since Washington was consistently preoccupied with seemingly more prevalent issues, it is suggested that the messages would not have even been taken seriously by the officials in the capitol (Prados, 166). "The breaking of Purple, though unable to prevent Pearl Harbor, later yielded astonishing insights into Hitler’s plans, gleaned from the messages of the Japanese ambassador in Berlin; All of this noticeably shortened the conflict" (FA 151).

There remains yet another reason why the US wasn’t ready for and didn’t believe that there would be an attack at Pearl Harbor. The traffic analysis reports taken in the four day span surrounding December 7, there was no communication between any of the Japanese carriers. The US concluded that this meat that the carriers were back in home waters. How the Japanese had outwitted the US for in fact "six of the carriers throught to be in home waters were in fact plowing the seas north of Hawaii "(FA 147).

Also in 1942, the United States received many purple messages forecasting an attack at "AF." At the time, the mid-Pacific radio net was intercepting sixty percent of the Imperial Navy’s messages. Furthermore, only about forty percent of the messages were being read. The one main advantage the cryptanalysts had was that they knew the meanings that the Japanese attached to a number of geographical designators, including "AF." Americans presumed that "AF" stood for Midway, but in order to figure out what AF stood for exactly, Nimitz told his operator to send a coded message, in a code that Japan had already broken, that Midway island was out of water. Sure enough, hours later the US received a PURPLE cipher that said "AF is out of water." Indeed "AF" meant Midway. Nimitz then sent his fleet to Midway and how surprised and punished the Japanese were when they arrived. History considers this US victory as one of the most decisive battles of war, as Japan's offensive power at sea was nearly destroyed.

Being aware of Japanese intentions also helped to bring about the death of Admiral Yamamoto, the Commander in Chief of the Japanese navy. Purple intercepted ciphers gave word that Yamamoto was to visit the Solomon islands. The exact details of his travels were also part of the message. The American decided to shoot him down. (Hidden War 130).

After PURPLE was broken in 1941, the United States faces another dilemma as to who should know and who should read the decrypted Japanese signals. The following thirteen people were given viewing rights: President Roosevelt, Secretary of State, War and Navy, Chiefs of Staff of Army and Navy and the Intelligence and War Plans Chiefs of the Army and Navy. The obvious dilemma is that if too many people knew that the Americans had broken Purple, word would leak out and Japan would change the code. This would shut the Americans out of all communication interception.

Hans Thomsen, a German spy, discovered that the Americans were breaking PURPLE. He passed this information onto the Japanese, but they were too ignorant and confident to believe that the Americans could break their code.

After the Battle of Midway, the Americans feared that the success with Purple would be compromised. On Sunday June 7, a front-page story of the Chicago Tribune claimed that the Americans had known the details of Japan’s plan to attack Midway. After much investigation, it was concluded that no one from the Navy Department spoke to any Chicago Tribune reporters…the leak was from somewhere else.

The leak was eventually traced to the Chicago Tribune reporter Stanley Johnston, by way of Commander Morton T. Seligman. Seligman was a former executive officer of the Lexington and shared a cabin with Johnston. Apparently Seligman allowed Johnston to see classified dispatches and one of them was Nimitz’s Midway warning. After taking notes on the message, Johnston left the ship to fly to Chicago.

Inside the Navy, it was argued that the Japanese changed all of their codes after Midway as a consequence of the Chicago Tribune affair. While the Japanese did change some codes and communication practices after Midway, the fleet code was left untouched. It was changed before Midway and would be changed before Midway and would be changed again, but it was out of routine, not as an emergency effort to protect Purple. In other words, the Japanese didn’t know that Purple had been broken. Finally, in 1942, Japan was forced to create a new codebook, as it was obvious that the US had broken Purple.

Purple was a cipher used by Japan during World War Two to code diplomatic messages to various embassies throughout the world. The United States worked solely to untangle and decipher the super-enciphered signals they intercepted from the

Japanese. Once the United States had created a "shadow machine", a Purple machine of their own, they were soon after able to decode the various messages they intercepted. These signals gave them an abundance of important information concerning Japan's plans for war and their scheduled locations of attack, however, the signals didn't carry any information about the attack on Pearl Harbor, at least none that was interpreted in that way. Thus Japan used other codes to transmit messages as well, and the interest in Purple had drawn away all concern for decoding the intercepted messages not transmitted in other ciphers. Because of this, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was inevitable. After the attack, decoding measures on all intercepted codes no matter what the cipher, were heightened and increased. Once war was declared, the United States continued to use the intercepted information to figure out where the Japanese fleet was stationed, headed and set to attack. As a result, the United States surprised Japan at Midway and American victory there proved to be very decisive and boosted American morale. Throughout the war, the United States made various surprise attacks on Japan due to the knowledge they had from Purple ciphers. This ended though, when Japan stopped using Purple in 1943.

Cryptology was a key factor in the US’s victory in WWII. One expert stated that it shortened the was by a year. It didn’t take long for the US and other nations to realize that cryptanalysis is "the cheapest, latest, and truest source of information" (Kahn, 613). Cryptology became one of the world’s most important sources of secret intelligence in World War II. Vice Admiral Walter S. Anderson, the former director of Naval Intelligence summed it up best when he said, "[Cryptology] won the war!" (Kahn 613).

Hans Thomsen, a German spy, discovered that the Americans were breaking PURPLE. He passed this information onto the Japanese, but they were too ignorant and confident to believe that the Americans could break their code.

After the Battle of Midway, the Americans feared that the success with Purple would be compromised. On Sunday June 7, a front-page story of the Chicago Tribune claimed that the Americans had known the details of Japan’s plan to attack Midway. After much investigation, it was concluded that no one from the Navy Department spoke to any Chicago Tribune reporters…the leak was from somewhere else.

The leak was eventually traced to the Chicago Tribune reporter Stanley Johnston, by way of Commander Morton T. Seligman. Seligman was a former executive officer of the Lexington and shared a cabin with Johnston. Apparently Seligman allowed Johnston to see classified dispatches and one of them was Nimitz’s Midway warning. After taking notes on the message, Johnston left the ship to fly to Chicago.

Inside the Navy, it was argued that the Japanese changed all of their codes after Midway as a consequence of the Chicago Tribune affair. While the Japanese did change some codes and communication practices after Midway, the fleet code was left untouched. It was changed before Midway and would be changed before Midway and would be changed again, but it was out of routine, not as an emergency effort to protect Purple. In other words, the Japanese didn’t know that Purple had been broken. Finally, in 1942, Japan was forced to create a new codebook, as it was obvious that the US had broken Purple.

Purple was a cipher used by Japan during World War Two to code diplomatic messages to various embassies throughout the world. The United States worked solely to untangle and decipher the super-enciphered signals they intercepted from the

Japanese. Once the United States had created a "shadow machine", a Purple machine of their own, they were soon after able to decode the various messages they intercepted. These signals gave them an abundance of important information concerning Japan's plans for war and their scheduled locations of attack, however, the signals didn't carry any information about the attack on Pearl Harbor, at least none that was interpreted in that way. Thus Japan used other codes to transmit messages as well, and the interest in Purple had drawn away all concern for decoding the intercepted messages not transmitted in other ciphers. Because of this, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was inevitable. After the attack, decoding measures on all intercepted codes no matter what the cipher, were heightened and increased. Once war was declared, the United States continued to use the intercepted information to figure out where the Japanese fleet was stationed, headed and set to attack. As a result, the United States surprised Japan at Midway and American victory there proved to be very decisive and boosted American morale. Throughout the war, the United States made various surprise attacks on Japan due to the knowledge they had from Purple ciphers. This ended though, when Japan stopped using Purple in 1943.